Webscraping techniques with R

Current challenges of webscraping

Numerous social networks recently decided to seal off their APIs more strongly and, for example, to offer them only in exchange for payment (or not at all). This increasingly limits the possibility for scientists to systematically capture important parts of digital discourse and to examine its influence on society. The lasting consequences of such decisions are expected to become more evident in the upcoming months and years, yet an immediate effect is already observable: The relevance of webscraping is on the rise again. As a means to replace the sealed-off APIs, many programmers, especially with regard to X (Twitter), resorted to systematically retrieving data via the X website – apparently at such a high frequency that Elon Musk’s X (Twitter) decided to put all of the website’s posts behind a login wall, making it more difficult to capture X’s (Twitter) data via scraping (Binder 2023).

This is a step back: In the past, many social platforms offered an API with (often) free quotas precisely to avoid the burden of webscraping on servers (Khder 2021, p.147). Moreover, webscraping comes with a variety of ethical, technical and legal concerns and questions (see Khder 2021). Even if one is only interested in a fraction of the publicly accessible data, webscraping requires capturing the data of the entire website instead of merely extracting the relevant information: Thus, significantly more data is collected than is necessary, for example, to provide a scientific answer to a hypothesis. Images are loaded, clicks are simulated – allowing the reconstruction of individual user behavior.

While this chapter shows you the ropes of responsible webscraping, it is critical to emphasize that is primarily the providers of social networks and websites who are called upon to offer the interfaces to their data for civil society and science in a suitable manner – after all, their online presence significantly shapes public discourse. This influence must be critically monitored and analyzed, which is why monitoring for research purposes must be supported. Currently many platform operators are resisting this responsibility and the need for transparency – let’s hope the Digital Services Act will improve that situation by forcing platform operators to enable data access (see EDMO 2023; AlgorithmWatch 2023).

What you will learn in this chapter

This chapter therefore aims to highlight three things:

- how to access such content, using concrete examples;

- how to deal with scraped data within the scope of one’s own responsibility to prevent overloading web servers and

- to access data responsibly and according to modern standards.

To collect data via webscraping (1), you will learn how to use the programming language R and the library rvest, using the tidy principles Wickham 2014. Intended for beginners as well as advanced programmers, this is meant to make the code presented here easy to access and analyze. Additional references, links and tutorials are included throughout.

Webscraping: The current state

Meanwhile numerous packages for programming languages are available, which simplify the collection of data significantly. In the Python world Beautiful Soup is one of the most important program libraries, in the R universe rvest takes a key role: Both libraries allow you to capture data from static web pages and extract elements from it.

Other programming languages and associated libraries also enable comprehensive web scraping -- for example, Puppeteer is a good way to capture both static and dynamic web pages via Node.js. For the purposes of this article, we will take a comprehensive look at the rvest package and its capabilities -- and also point out options when, for example, pages do not have static elements but should still be captured. For an example of how to use puppeteer see this chapter in the knowledge hub.

In this chapter, you will be introduced to the rvest package and its capabilities – and learn about options on how to scrape dynamic pages.

To do so, we will use two sites as examples: the pro-Russian disinformation website Anti-Spiegel.ru of conspiracy ideologist Thomas Röper (see Balzer 2022) and the conspiracy ideology media portal AUF1 (see Scherndl and Thom 2023) run by right-wing extremist Stefan Magnet. While Röper’s Anti-Spiegel is a static website (operated with Wordpress) – i.e. a website which is rendered by the server – AUF1 is a website which, like many other modern websites, is only partially rendered and only fully loaded in the browser.

Note

An overview of the different principles of web content delivery can be found in this article.

Both examples are well suited to demonstrate different ways of scraping with rvest. Content-wise, they influence online discourse with anti-democratic worldviews and disinformation regarding, for example, the Russian war on Ukraine or the topic of vaccinations and pandemics. Their content continues to influence (at least parts of) society in the German-speaking world. Therefore, they not only serve as an example for data collection, but also show that it is important to deeply investigate such platforms from a societal cohesion perspective.

Diving into a pro-Russian disinformation world

The Russian propagandist Thomas Röper published numerous articles on his website in which he belittles the consequences of, for example, the Russian war of aggression against the Ukraine and denies war crimes (see Journalist 2022). He not only writes his own articles, but also publishes news reports from the Russian news agency TASS and the Kremlin’s media outlet Russia Today. To determine which domains are cited particularly frequently, these sections will provide guidance on the necessary steps. Additionally, potential challenges during the scraping process will be addressed.

library(rvest)

# Several packages of the **tidyverse** will be used

# for example `dplyr` for data manipulation or `ggplot` to visualize the data we accessed.

# Therefore, the whole tidyverse is being loaded.

library(tidyverse)

# Glue is used for better data annotations in the graphs. This is optional.

library(glue)

page <- read_html("https://www.anti-spiegel.ru/category/aktuelles/")

On his website we can find a link with which we can access all his articles. rvest can make the data usable for our further analysis. Via read_html we can read a page, then we can access different elements of the web page via the function html_elements(). The easiest way is to use so called CSS selectors to choose the section which should be extracted: CSS selectors are different patterns which can be used to access different elements of an HTML page.

Note

An overview of different CSS selector patterns can be found at W3Schools.

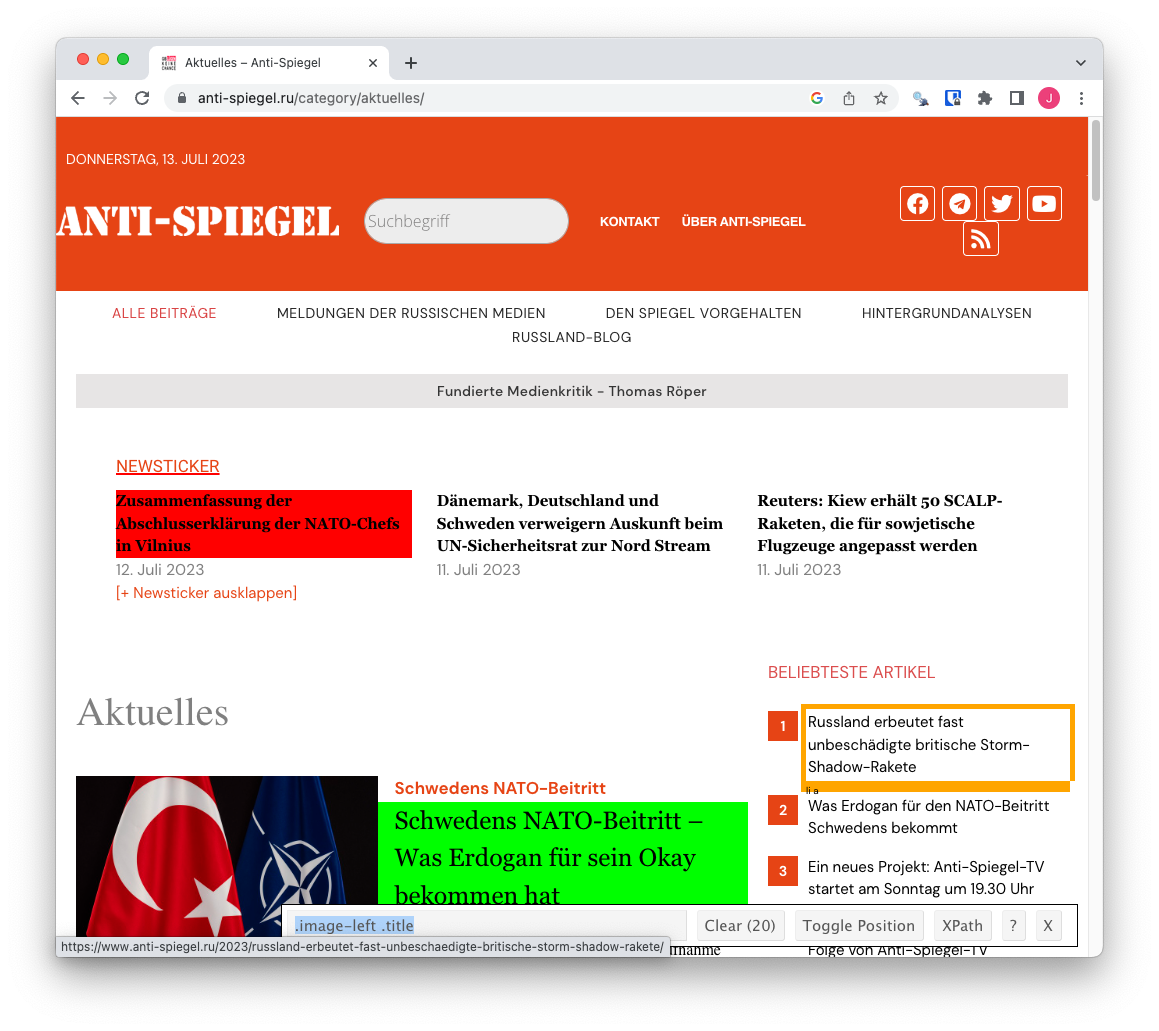

To make it easier to choose the right selectors, you can use the Google Chrome extension SelectorGadget: By simply selecting and deselecting on a web page, the right CSS selector for the right segment can often be found quickly, as in the example of the title of each article here. Selecting the title and deselecting the ticker shows, that currently 20 titles are being highlighted using the selector image-left .title

Selectorgadget example on Röpers page

Selectorgadget example on Röpers page

Using the CSS selectors, you can now determine the segments that are relevant to you – afterwards, you will write a function that will store all the relevant information in one record. rvest also has useful support functions here, such as html_text(). This function allows you to convert html types into simple text vectors; html_text2() extends this function and additionally removes unnecessary white spaces.

Hint

You can find a good introduction to rvest and documentation on its main page.

The most important functions for this examples case are html_elements() and html_attr() – they allow you to extract elements and attributes (for example, the link from the href attribute of a <a> node). rvest makes use of many functions of the xml2 package, so it’s worth having a look at its documentation.

Note

For example, html_structure() from xml2 is useful to get an overview of the structure of a web page.

page %>%

html_elements(".image-left .title") %>%

html_text()

[1] "Der manipulierte Whistleblower-Bericht"

[2] "Die UNO als Instrument des Westens"

[3] "Der Bevölkerungsrückgang macht die Ukraine wirklich zum „Land 404“"

[4] "Wem ist nichts mehr heilig?"

[5] "Was Spiegel-Leser über das Treffen von Lukaschenko und Putin (nicht) erfahren"

[6] "Droht eine Eskalation zwischen den USA und Russland?"

[7] "Die Geschäfte der Bidens in der Ukraine"

[8] "Der Schwarze Peter geht an Kiew"

[9] "Käuferin von Hunter Bidens Bildern bekommt einen Posten in der US-Regierung"

[10] "Internetkonzerne, KI und totale Zensur und Kontrolle"

[11] "Estland verbietet Feiern zum Jahrestag der Befreiung von Nazi-Deutschland"

[12] "Die Bidens: Eine schrecklich nette Familie"

[13] "Die Versuche der USA, die NATO auf den Pazifik auszudehnen"

[14] "Die BRICS laden 70 Staatschefs ein, aber niemanden aus dem Westen"

[15] "Mein neues Buch ist jetzt im Handel"

[16] "Putin schreibt einen Artikel über die Beziehungen zu Afrika"

[17] "Wie die US-Demokraten die Korruptionsskandale des Biden-Clans zu verschleiern versuchen"

[18] "Was wird aus dem Getreideabkommen?"

[19] "Ukrainische Gegenoffensive laut Putin gescheitert: Die Ereignisse des Wochenendes"

[20] "Unsere Fahrt an die Front in Saporoschschje"

In most cases, not all content relevant to the investigation can be found on one page but will be distributed over several pages. In this example, you can find over 200 pages that can be extracted. Either way, you can either manually compile the pages you want to scrape or extract them automatically and reproducibly from the overview page.

Next page example on Röpers page

Next page example on Röpers page

Using the CSS selector .page-numbers we can extract all page numbers - however, here we also extract the Next navigation object. To extract the relevant information from these objects (here for example the last number) you must use regular expressions. Regular expressions are certain terms and symbols that search for patterns in a text, in the following example a number that is not followed by another number.

A useful extension for R is Regexplain. This add-on for RStudio allows to test various regular expressions directly in the interface. Many tips and tools can also be found online, for example regex101.

last_page_nmbr <- page %>%

html_elements(".page-numbers") %>%

html_text() %>%

# Collapse the vector to one string separated by a space.

paste(collapse = " ") %>%

# Regular expression for selecting the last digit in a string.

str_extract("(\\d+)(?!.*\\d)")

In the next step you can now write your own function that extracts the relevant sections from each overview page. The result is output as a tibble – a data.frame object that also provides a quick overview of the data in the console and can be used for. To avoid scraping later, you should store the raw HTML in a column of the tibble. This also allows you to extract additional data, such as the number of comments, later. Such a procedure is also a best practice, as it allows you to avoid a larger server load for the site operator due to multiple scraping.

get_article_overview <- function(url) {

page <- read_html(url)

tibble(

title = page %>%

html_elements(".image-left .title") %>%

html_text(),

subtitle = page %>%

html_elements(".image-left .dachzeile") %>%

html_text(),

url = page %>%

html_elements(".image-left .title") %>%

html_attr("href"),

date = page %>%

html_elements(".image-left .date") %>%

# Dates are presented in a date-mont-year format, which is common in Germany.

# The locale must be installed on your computer, in this case "de_DE.UTF-8".

dmy(locale = "de_DE.UTF-8"),

raw = page %>%

html_elements(".image-left .listing-item") %>%

# You want to store this as `character` because a `tibble` does not accept a `xml_nodeset` item,

# which also points to a serialized object stored in memory.

# You can reserialze this object again using `read_html()`.

as.character()

)

}

Using your just written function and the previously extracted last page number, a vector of all overview pages can now be created. Afterwards, using the function map() from the package purrr, your function can be applied to all pages and in turn and tibble can be formed from them. (map_dfr() applies the function and forms a data.frame(df) by merging the results row by row (r)).

all_articles_summary <- read_rds("data/all_articles_summary.rds")

url_part <- "https://www.anti-spiegel.ru/category/aktuelles/?dps_paged="

all_page_urls <- map_chr(1:last_page_nmbr,

~paste0(url_part, .x))

all_articles_summary <- map_dfr(all_page_urls, get_article_overview)

all_articles_summary

Because R and rvest work only sequentially via map() the command can often take a long time: one web page is called, scraped and then the next web page is called and scraped. The internet speed, the computing power as well as possible blockades by site operators can cause individual connections to get aborted, or the command would take so long that it is no longer practicable to scrape a web page.

You can improve the scraping process by parallelization: It is important to keep in mind that parallelization leads to additional load on the affected web servers. Several pages are opened in parallel – more in the chapter on parallelization.

Webscraping is a gray area and is regulated differently from country to country or was part of court decisions. Even if site operators want to prevent web scraping, for example through their terms of use, it may still be justified and permitted, e.g. for consumer protection reasons. This is the case in Germany, for example (German Federal Court of Justice 2014).

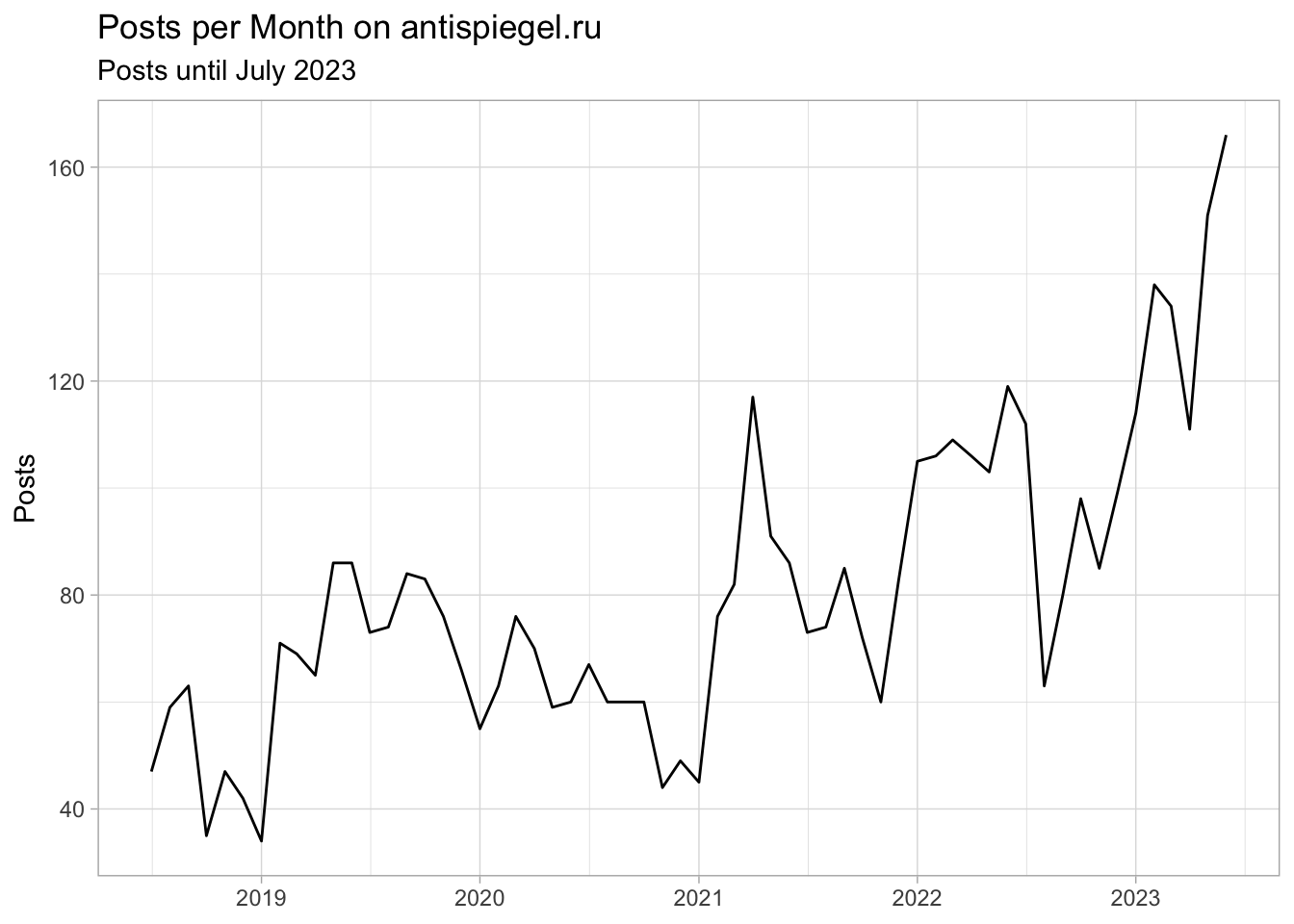

Analyzing scraped data and next steps

Since the data is in tidy format (see Wickham 2014), further analysis and presentation via the packages of the tidyverse is simple and clear. Using ggplot we can, for example, display the number of posts that were written per month.

all_articles_summary %>%

mutate(month = floor_date(date, "month")) %>%

count(month) %>%

# It is recommended to filter out the current month

# because it risks being misrepresented in the dataset.

filter(month != today() %>% floor_date("month")) %>%

ggplot(aes(month, n)) +

geom_line() +

theme_light() +

labs(title = "Posts per Month on antispiegel.ru",

subtitle = glue("Posts until {today() %>% format('%B %Y')}"),

y = "Posts", x = NULL)

Number of article per month on the german pro-russion propaganda website antispiegel.ru by Thomas Röper

Number of article per month on the german pro-russion propaganda website antispiegel.ru by Thomas Röper

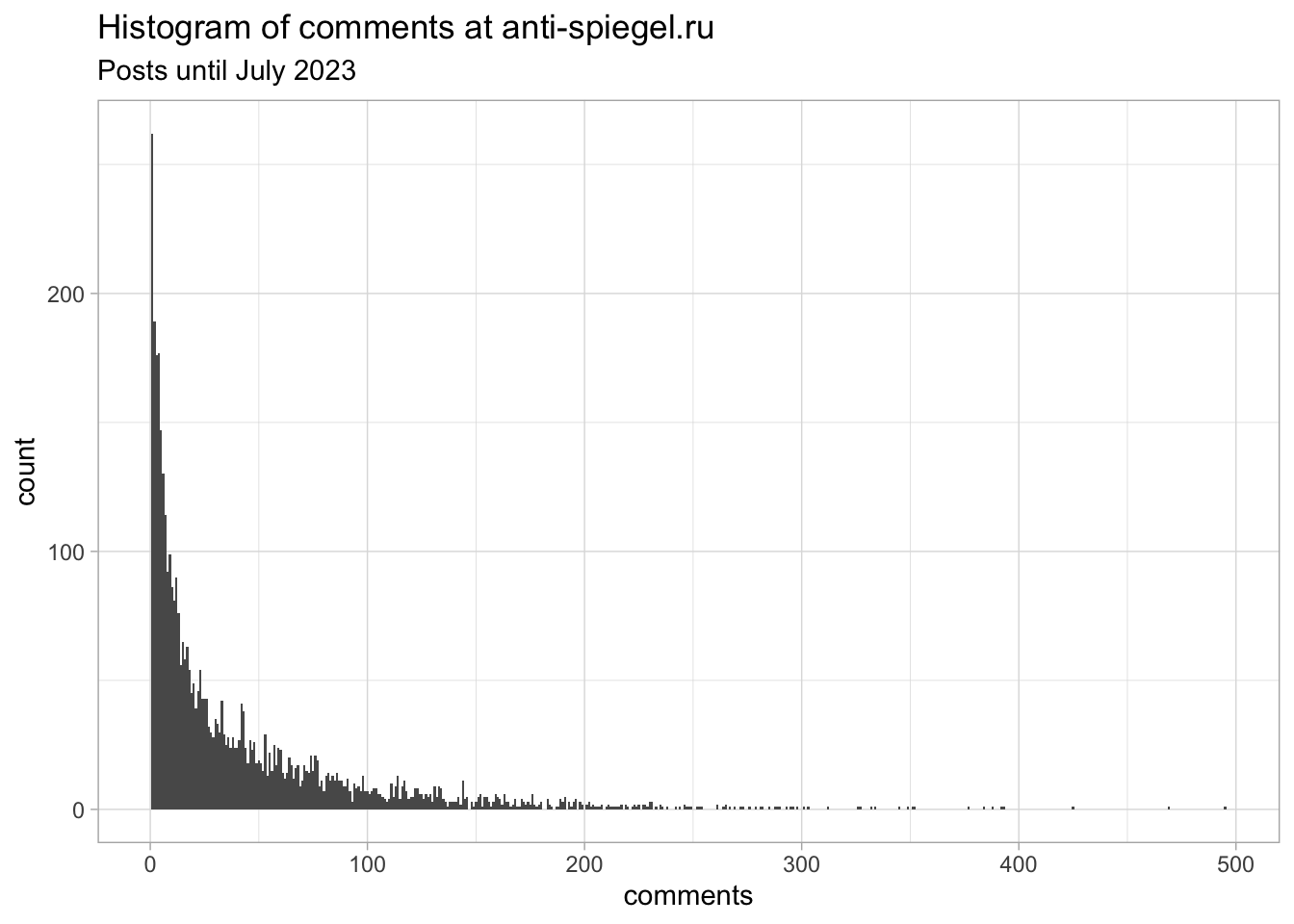

The example of Röper illustrates how to handle data from particularly active sites. While you didn’t scrape the number of comments via your function, you can do so by extracting the number of comments from the raw values in the column raw. Thus, you avoid further scraping of the data.

Note that not all articles contain comments – if comments are missing, there is also no html_element with comments, leading to fewer comment fields than e. g. title fields and a tibble cannot be constructed.

The reason why we did this is also because not all articles contain comments – if comments are missing, there is also no html_element with comments, leading to fewer comment fields then e. g. title fields and a tibble can’t be constructed.

get_comments <- function(raw_data) {

element <- read_html(raw_data)

html_elements(element, ".comments-link a") %>% html_text(trim = TRUE)

}

article_comments <- all_articles_summary %>%

# You should wrap this in “possibly” to prevent errors from stopping the code execution.

# If you can’t extract a comment string, you give it a NA value.

mutate(comments_string = map(raw,

possibly(get_comments,

otherwise = NA_character_))) %>%

unnest(comments_string) %>%

mutate(comments = str_extract(comments_string, "\\d+") %>% as.numeric())

article_comments %>%

ggplot(aes(comments)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1) +

theme_light() +

labs(title = "Histogram of comments at anti-spiegel.ru",

subtitle = glue("Posts until {today() %>% format('%B %Y')}"))

Histogram of number of comments under each article from anti-spiegel.ru

Histogram of number of comments under each article from anti-spiegel.ru

As you can see, the most discussed article has 495 (r article_comments %>% top_n(1, comments) %>% pull(comments)) user comments with the headline "Putins Rede zur Vereinigung Russlands mit den ehemals ukrainischen Gebieten" (r article_comments %>% top_n(1, comments) %>% pull(title)) from 01. October 2022 (r article_comments %>% top_n(1, comments) %>% pull(date) %>% format("%d. %B %Y")). Most of the articles are not commented.

Scraping huge datasets via parallelization

Previously, you learned how to scrape content sequentially and you were able to extract 20 article summaries per scraped page. If you now want to scrape not only the preview of the articles but all pages, the number of pages to be scrapped increases significantly.

With the package furrr you can improve the scraping process by parallelization: It is important to keep in mind that parallelization leads to additional load on the affected web servers. Several pages are opened in parallel. It is therefore important to include pauses in the function definition to distribute the load and to keep the number of cores used for parallelization low - in this case a maximum of five workers working in parallel.

Via plan(mulitsession) you specify that the following code should be executed in parallel sessions - this is not always faster because the sessions must be started and ended. Small data sets are possibly better suited with a sequential approach.

All articles of Anti-Spiegel.ru should be scrapped and analyzed – however, in first tests it could be noticed that a lot of content on Röper’s page is repeated. For example, under each article there is a reference to his book published by J.K-Fischer Verlag. However, this advertisement for his own publication is separated from the rest of the text by a dividing line.

Using simple CSS selectors, however, this part cannot be separated from the rest -- though rvest can be used with extended xpath selectors. These allow us, for example, to only scrape <p> nodes which are followed by a <hr> node (the separator).

Hint

Cheat sheets for using xpath selectors are available here.

page <- read_html("https://www.anti-spiegel.ru/2023/daenemark-deutschland-und-schweden-verweigern-auskunft-beim-un-sicherheitsrat-zur-nord-stream/")

page %>%

html_elements(xpath = "//p[following-sibling::hr]") %>%

html_text() %>%

paste(collapse = "\n")

[1] "UNO, 11. Juli. TASS/ Vertreter Dänemarks, Deutschlands und Schwedens nehmen am Dienstag nicht an der von Russland einberufenen Sitzung des UN-Sicherheitsrates über die Sprengung der Gaspipelines Nord Stream und Nord Stream-2 teil, berichtet der TASS-Korrespondent.\nZuvor hatte der erste stellvertretende ständige Vertreter Russlands bei dem Weltgremium, Dmitri Poljanski, erklärt, die russische Delegation habe für den 11. Juli eine offene Sitzung des UN-Sicherheitsrates zum Thema der Spreungung der Nord-Stream-Pipeline beantragt. Dem Diplomaten zufolge hat Russland „die britische Präsidentschaft gebeten, Vertreter“ der drei Länder – Dänemark, Deutschland und Schweden – einzuladen, die die Sabotage der Gaspipelines untersuchen, um darüber zu berichten."

Unfortunately, however, not all entries have this separator, so you won’t get results for some entries with this xpath selector – for example with this article.

page <- read_html("https://www.anti-spiegel.ru/2022/ab-freitag-gibt-es-russisches-gas-nur-noch-fuer-rubel-die-details-von-putins-dekret-und-was-es-bedeutet/")

page %>%

html_elements(xpath = "//p[following-sibling::hr]") %>%

html_text() %>%

paste(collapse = "\n")

[1] ""

Often you will encounter such problems when webscraping, so it is important to work with a lot of examples first and test the code extensively. In this case, you scrape the data with a CSS selector and remove the always same advertising paragraphs with simple regular expressions. As mentioned above you create a function with pauses of 5 seconds (Sys.sleep(5)) on 5 processors at the same time.

all_articles_full <- read_rds("data/all_articles_full.rds")

library(furrr)

plan(multisession, workers = 5)

get_article_data <- function(url) {

page <- read_html(url)

# Pause for 5 seconds

Sys.sleep(5)

# regex for addendum beginning

pattern_addendum <- "In meinem neuen Buch.*$|Das Buch ist aktuell erschienen.*$"

tibble(

url = url,

raw = page %>%

html_elements(".article__content > p") %>%

# `html_text2` to trim the data and remove unnecessary white spaces.

as.character() %>%

str_remove(pattern_addendum) %>%

paste0(collapse = ""),

text = page %>%

html_elements(".article__content > p") %>%

html_text() %>%

str_remove(pattern_addendum) %>%

paste(collapse = "\n"),

datetime = page %>%

html_elements(".article-meta__date-time") %>%

html_text2() %>% # <1>

dmy_hm(locale = "de_DE.UTF-8")

)

}

all_articles_full <- future_map(all_articles_summary %>%

filter(date >= "2022-01-01") %>% pull(url),

# Wrapped in `try` to prevent errors from failing the whole process –

# failed scrapings can be removed afterwards.

~try(get_article_data(.x)), .progress = TRUE)

Next, you will implement further measures to prevent your code from breaking prematurely and losing the already scraped content. Since the idea is that you wrap the function in a try, even errors do not lead to an abortion of the scraping. Errors can, however, mean connection failures. These failures can be fixed in a further process – if errors occur too often, it is recommended to optimize the code or to have longer pause times during the scraping to avoid overloading the servers.

To avoid scraping all websites, you should set clear limits for data collection, in this example this will be data from 2022 onwards – in a final step, you want to determine which domains are particularly frequently cited by Thomas Röper.

all_articles_df <- all_articles_full %>%

keep(is_tibble) %>%

bind_rows()

get_links <- function(raw_html) {

element <- read_html(raw_html)

element %>% html_elements("a") %>% html_attr("href")

}

get_domain <- function(link) {

# regex for domain

domain_pattern <- "^(?:[^@\\/\\n]+@)?([^:\\/?\\n]+)"

link %>%

str_remove("http://|https://") %>%

str_remove("^www.") %>%

str_extract(domain_pattern)

}

all_articles_df %>%

mutate(links = map(raw, possibly(get_links, otherwise = NA_character_))) %>%

mutate(domain = map(links, possibly(get_domain, otherwise = NA_character_))) %>%

unnest(domain) %>%

count(domain, sort = TRUE) %>%

head(10) %>%

# `kable()` from the library `knitr` is only used in this context to generate an html table

knitr::kable() # <1>

Table 1: Most shared domains by anti-spiegel.ru

| domain | n |

|---|---|

| anti-spiegel.ru | 5793 |

| tass.ru | 1219 |

| spiegel.de | 611 |

| vesti7.ru | 303 |

| t.me | 245 |

| vesti.ru | 191 |

| deutsch.rt.com | 137 |

| youtube.com | 126 |

| kremlin.ru | 85 |

| mid.ru | 82 |

To sum up, your first webscraping case highlighted that Röper refers particularly frequently to the Russian news agency TASS and the Kremlin outlet RT DE. From a research perspective, it is noteworthy that there are European sanctions and a broadcast ban against RT DE (see Spiegel 2022; Der Standard 2022) – yet our test case continues to share them (for possible explanations why, see Baeck et al. 2023). Among the most shared domains is also t.me of the platform and messenger service Telegram – this platform is used by Röper particularly often, along with YouTube. Incidentally, if you hadn’t removed the advertising block, J.K. Fischer Verlag would rank first in this table.

Second example: AUF1 as a dynamic website

Röper’s website is comparatively simple in design. The Wordpress site is statically generated. The web server simply outputs HTML pages, which can be downloaded and checked.

Not all sites are built this way, in fact it has probably become more common to host dynamic websites. This is also the case with the Austrian website AUF1 of the right-wing extremist and conspiracy ideologue Stefan Magnet (see Scherndl and Thom 2023), which quickly became one of the most widespread websites of pandemic deniers in the German-speaking world from autumn 2021.

Content scraped via rvest shows that reactions cannot be scraped – it simply shows an empty value.

AUF1 Screenshot with Reactions

AUF1 Screenshot with Reactions

rndm_article <- "https://auf1.tv/auf1-spezial/fpoe-gesundheitssprecher-kaniak-zu-who-plaenen-impf-zwang-auch-ohne-pandemie"

page <- read_html(rndm_article)

page %>% html_elements(".reactions")

{xml_nodeset (0)}

A workaround here is to simulate a browser, which calls the page and executes all content. One possibility for this would be to use Selenium. This is a framework for automated software testing of web applications in different browsers –and you can use it for advanced web scraping, too.

With RSelenium you can start different browsers (to replicate this example, you should use Firefox, the corresponding binaries are downloaded via wdman). Afterwards you navigate to the corresponding page and then load the web page contents of the finished page back into rvest via read_html. Then, you can work as before and analyze different contents.

#| label: tbl-emojis

#| tbl-cap: Reactions used on a random AUF1 article

library(RSelenium)

# start the browser

# check if java and openjdk is installed first

# wdman will install the rest

rD <- rsDriver(browser = "firefox", verbose = FALSE)

rD$client$navigate(rndm_article)

# Setting a _sleep_ for 3 seconds to guarantee that the page has finished loading.

Sys.sleep(3)

# We can load in the Selenium page source directly into rvest and use it as before

page <- read_html(rD$client$getPageSource()[[1]])

tibble(

emoji = page %>%

html_elements(".reactions .emoji") %>%

html_text() %>%

unique(),

count = page %>%

html_elements(".reactions .count") %>%

html_text() %>%

as.integer()

) %>%

arrange(-count) %>%

pivot_wider(names_from = emoji, values_from = count) %>%

# Just for styling purposes, this looks more clean in the browser

knitr::kable(align = "c")

Table 2: Reactions used on a random AUF1 article

| 👍🏻 | ❤️ | 💪🏻 | 😮 | 😢 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 489 | 229 | 131 | 64 | 58 |

With RSelenium you can extract data which wouldn’t be possible via rvest alone. You could now write a function to extract all emojis on videos and find the video that had the most interactions – this is not something, we will show in this chapter, but should be provided for interested (social) scientists and civil society researchers to build webscraping projects on their own. Even for advanced and dynamic web pages.

One last thing: Since you are using an automated browser on Desktop, you need to close it after reading in your data. Otherwise, the browser will keep on running in the background. You should also close your server that provided the background tasks for running Selenium.

rD$client$close()

rD$server$stop()

Literature

-

AlgorithmWatch. (2023). DSA Must Empower Public Interest Research with Public Data Access. AlgorithmWatch. https://algorithmwatch.org/en/dsa-empower-public-interest-research-data-access/

-

Baeck, Jean-Philipp, Fromm, Anne, & Peters, Jean. (2023). Warum Russia Today trotz Sanktionen in Europa weiterläuft. correctiv.org. https://correctiv.org/aktuelles/russland-ukraine-2/2023/02/17/eu-sanktionen-gcore-russia-today/

-

Balzer, Erika. (2022). Desinformations-Medien: Der Anti-Spiegel - Russische Propaganda und Verschwörungsmythen. Belltower.News. https://www.belltower.news/desinformations-medien-der-anti-spiegel-russische-propaganda-und-verschwoerungsmythen-132357/

-

Binder, Matt. (2023). Elon Musk Claims Twitter Login Requirement Just 'Temporary'. Mashable. https://mashable.com/article/elon-musk-twitter-login-requirement-temporary

-

DerStandard. (2022). Bis zu 50.000 Euro Strafe für Verbreitung von russischem Staatssender RT – alleine FPÖ stimmt dagegen. DER STANDARD. https://www.derstandard.de/story/2000133980411/bis-50-000-euro-fuer-verbreitung-von-russischem-staatssender-rt

-

EDMO. (2023). Members of the EDMO Task Force on Disinformation on the War in Ukraine Submit Feedback to the EC Call for Evidence on the Provisions in the DSA Related to Data Access. EDMO. https://edmo.eu/2023/05/30/members-of-the-edmo-task-force-on-disinformation-on-the-war-in-ukraine-submit-feedback-to-the-ec-call-for-evidence-on-the-provisions-in-the-dsa-related-to-data-access/

-

Fung, Brian. (2023a). Academic Researchers Blast Twitter's Data Paywall as 'outrageously Expensive'. CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/05/tech/academic-researchers-blast-twitter-paywall/index.html

-

Fung, Brian. (2023b). Reddit Sparks Outrage after a Popular App Developer Said It Wants Him to Pay $20 Million a Year for Data Access. CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/01/tech/reddit-outrage-data-access-charge/index.html

-

German Federal Court of Justice. (2014). BGH, 30.04.2014 - I ZR 224/12. BGH.

-

Glez-Peña, Daniel, Lourenço, Anália, López-Fernández, Hugo, Reboiro-Jato, Miguel, & Fdez-Riverola, Florentino. (2014). Web Scraping Technologies in an API World. Briefings in Bioinformatics. https://academic.oup.com/bib/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/bib/bbt026

-

Journalist. (2022). Im Desinformationskrieg. journalist.de. https://www.journalist.de/startseite/detail/article/im-desinformationskrieg

-

Khder, Moaiad Ahmad. (2021). Web Scraping or Web Crawling: State of Art, Techniques, Approaches and Application. International Journal of Advances in Soft Computing & Its Applications, 13(3).

-

Scherndl, Gabriele, & Thom, Paulina. (2023). Was hinter dem österreichischen Verschwörungssender Auf1 steckt. correctiv.org. https://correctiv.org/faktencheck/hintergrund/2023/04/27/was-hinter-auf1-stefan-magnet-und-der-ausbreitung-des-oesterreichischen-verschwoerungssenders-steckt-desinformation-und-rechte-hetze/

-

Spiegel. (2022). Maßnahmen gegen russische Staatsmedien: Verbreitung von RT und Sputnik ist in der EU ab sofort verboten. Der Spiegel. https://www.spiegel.de/kultur/ukraine-krieg-verbreitung-von-rt-und-sputnik-ist-in-der-eu-ab-sofort-verboten-a-49597add-c2b2-44da-b1e4-6832d3ea824f

-

Wickham, Hadley. (2014). Tidy Data. The Journal of Statistical Software. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v59/i10/